Thoughts in the Context of the January 6 Hearings

In legal proceedings, the use of high-tech, impactful visuals is becoming an increasingly valuable method of enhancing the spoken word when it comes to presenting a narrative and building a legal case. Many businesses, including law firms, have used presentations in a variety of engagements and for many purposes for years; however, presentations have historically usually been clumsy foam-back enlargements or more often siloed to marketing and business development as a method to promote or sell services or products.

And while visual exhibits are indeed frequently leveraged in depositions, in mediation sessions, and for various court hearings, they are often displayed in the most banal of forms, appearing as hard copies in trial notebooks or papers shuffled around and handed out in conference rooms or during legal proceedings. Oftentimes, an entire document or transcript is distributed with a verbal reference to a particular line or quote. This is cumbersome and potentially ineffective, and in our digital age, it is increasingly problematic, given that judges, lawyers, mediators, juries, and the general public are joining proceedings virtually.

Let’s examine the basic purposes of visual aids in the legal world in the context of the January 6 hearings. Some of the functions include the following:

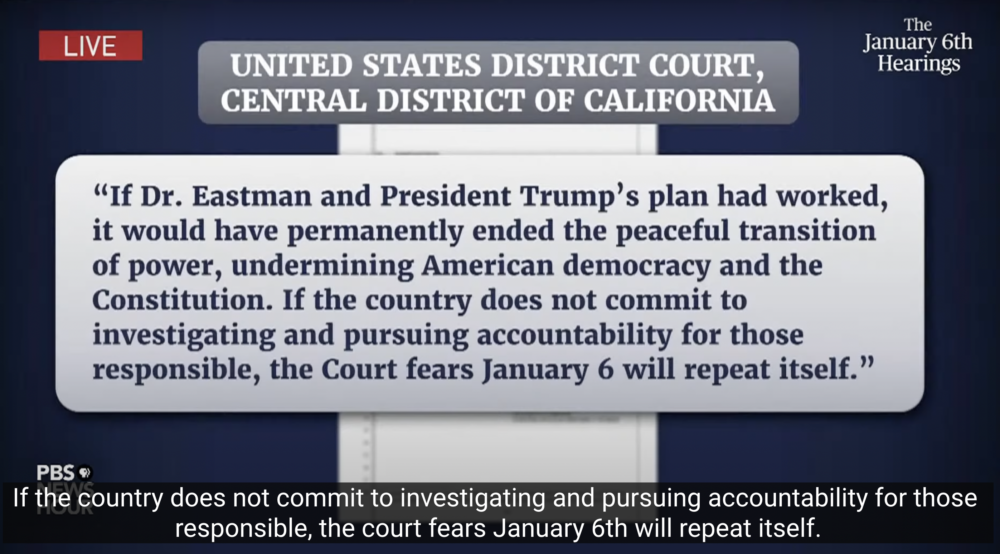

1. Emphasizing key facts.

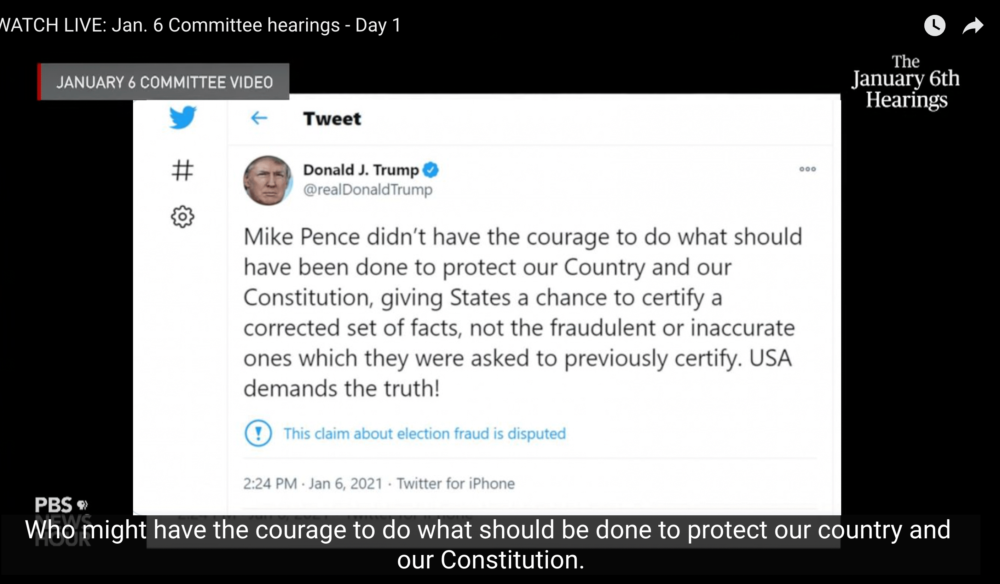

While some of what has been displayed is still technically written — such as printed emails, memos, and other documents — callouts (visual excerpts) are leveraged to emphasize important and relevant facts. In some instances, simple animations trigger multiple evidentiary quotes. These callouts establish hierarchy in a sea of content and words, directing the audience’s attention to critical takeaways.

2. Reenacting events.

Utilizing the contents from various depositions, the January 6 committee provided a three-dimensional rendering of what it was like to be in that explosive meeting in the Oval Office on January 3, 2021, including who in attendance was sitting, where they were sitting, and what was said. Instead of simply telling us what happened that day, the committee placed us in that room, enabling the listener to become the proverbial fly on the wall.

3. Building character.

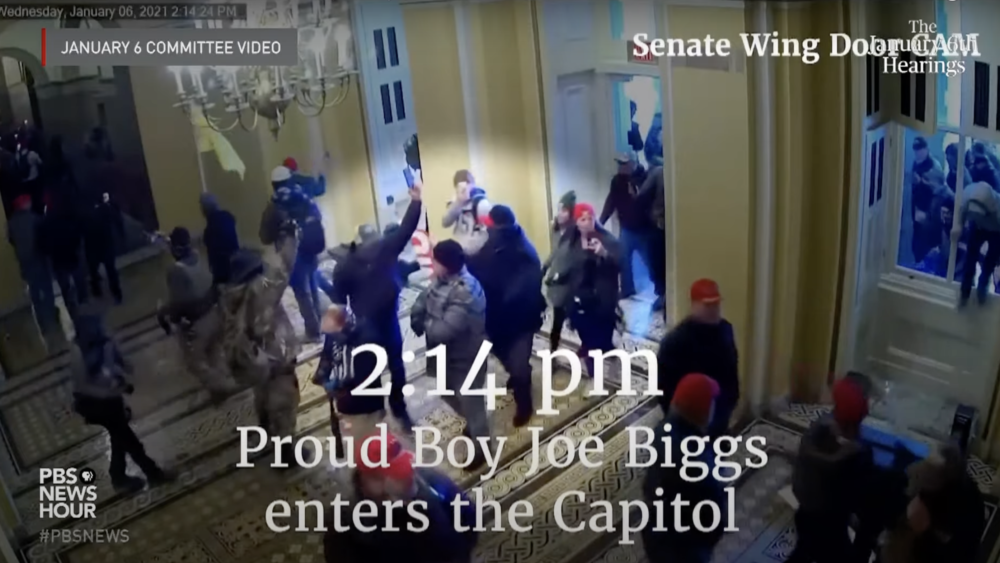

Photographic evidence, sound bites, and testimonies clearly depict who the players are: the good and the bad, the consistent and the contradictory. Choice of the photographs or video snippets to be utilized also play an important role in establishing reliance – or distrust – of a particular player in the story.

4. Creating a sense of time and space.

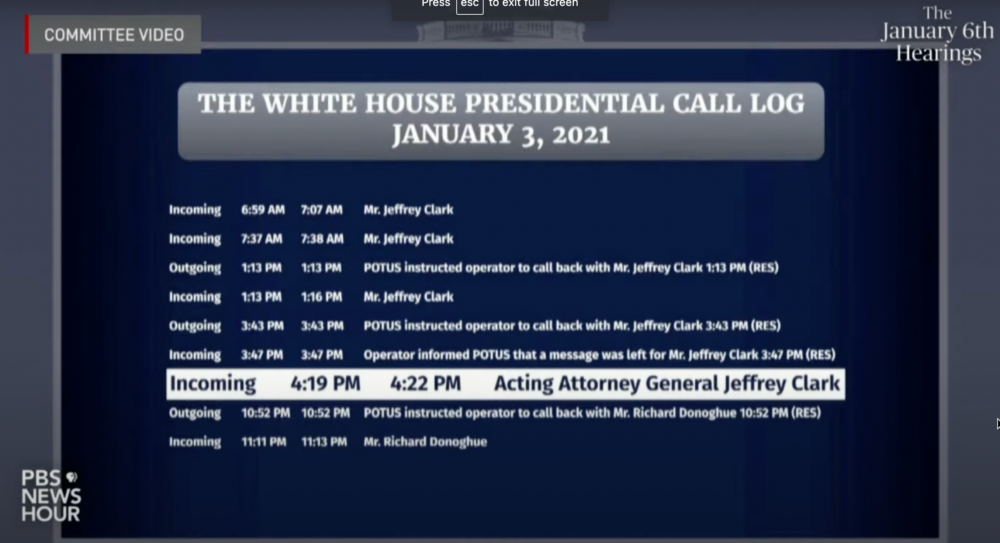

A single call log can tell us a great deal, but compiling multiple call logs, time-stamped videos, and testimonies effectively pieces together overlapping events into a single, clear narrative, affording a more comprehensive and much deeper chronology of what was going on concurrently that day, including insights into the causes and effects.

In the case of the January 6 hearings, we are quite literally seeing how facts and evidence, spanning a variety of media, can be synthesized to more effectively tell a nonfiction story. In other words, this compilation of media presents the facts and builds a case.

Combining a variety of media, including videos, audio recordings, emails, memos, text messages, and social media posts, in a single presentation gives the audience a better grasp on what happened that day. This is not only a more efficient way of presenting exhibits, but it also contributes to the narrative.

Visuals are 90% more effective than written or spoken words because they resonate with us more due to the way our brains retain information. With so many graphics and forms of media used, the January 6 hearings convey information that sticks with audiences for much longer than would mere discussions of facts and events.